Poor communication is a symptom, not a cause

Americans frequently come across as blunt, rude, and inappropriate in much of the world. We have a reputation for being close-minded and difficult to get along with. This is news to most Americans.

About a decade ago I wrote a book about successfully working in cross-cultural, international projects. I’m posting this chapter as I feel it’s especially relevant today, with so many of us working in multinational, distributed teams. This is part one from the chapter on communication. I hope you enjoy it.

How different cultures communicate

Germans, the Swiss, and other Westernized people such as the English have their own cultural reputation. Even so, I think it’s worse for Americans. American culture is very closed off and self-centric. At least European natives have the advantage of more diverse cultural exposure.

This chapter explores the role communication plays in multinational teams. Let’s start with a short story, about Jack, a Texan businessman visiting Thailand for the first time.

Jack and his host, Gan, conclude a few days of negotiations on a contract. There were a few missteps and mistakes, but Gan was tolerant and did his best to ignore his guest’s loud, boisterous manner and overly familiar gestures. Even so, both of them were relieved to sign the contract — likely worth a few million dollars in revenue to each of them.

Everything looked like it was going well and Jack felt a celebration was in order. As he loudly slapped the table in celebration, he pulled out two cigars, and casually offered one to Gan. Always respectful and polite, Gan genially accepted the cigar without smiling and declined the offer to light it. Then, Jack did the unthinkable. He leaned back in his chair, put his feet up on the table, and proceeded to light his cigar.

Gan stood up, dropped the contract in the trash, and with a perfunctory shallow bow, turned and walked out of the room. Jack was utterly clueless. He lost the deal and headed home without talking to Gan again.

Had he been more perceptive, he would have known he was on thin ice. Gan had often responded to Jack with gentle Thai cues. Sometimes his response lacked a characteristic smile. Other times he was silent, or stared directly in Jack’s eyes. At one point Gan had relayed an oblique story about how many Thai’s didn’t understand America’s brash culture, but the meaning was lost on Jack — he laughed it off, and said America was “the Wild West.” Likely, Jack thought it was a compliment.

It’s most likely that Jack was equally confused by Gan. Clearly, their meeting came to a surprising end. He probably thought Gan’s comments about the “Wild West” was just an excuse for him to act more like a cowboy. Unfortunately, it was that very same thick American skin that kept him from seeing what was developing.

If you’re new, welcome to Customer Obsessed Engineering! Every week I publish a new article, direct to your mailbox if you’re a subscriber. As a free subscriber you can read about half of every article, plus all of my free articles.

Anytime you'd like to read more, you can upgrade to a paid subscription.

Low-context and high-context

Team members in multinational projects come face-to-face with cultural differences every day. Most of the time, problems that crop up go unnoticed until too late. Maybe that’s once you’ve onboarded a remote team member, or maybe it’s after quality problems are “baked in” to a product. By then, the project is well on the road to failure.

Missing cultural cues in communication can quickly lead to misunderstandings. Communication around the world varies widely, along a spectrum defined on one end by low-context and the other by high-context communication. Western business cultures, dramatically represented by the United States, Germany, and Australia, rely on low context communication. This means predominantly use words to send a message, and it’s common in highly diverse cultures.

As many people with diverse backgrounds come together, the lowest common denominator survives as the principle means of communication. In the United States, English, more than anything else, is universally relied upon. It helps explain why long legal agreements have become typical of the U.S. — the written word represents the entire relationship.

In contrast, cultures belonging to the “BRICS” (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South America — and many other Eastern cultures) are intensely high context in their communication. They rely on rich cultural cues. These cues include formal and informal address, story telling, silence, body language, over-confirmation, timing, eye contact, and a host of other subtle behaviors that are completely lost on many Westerners.

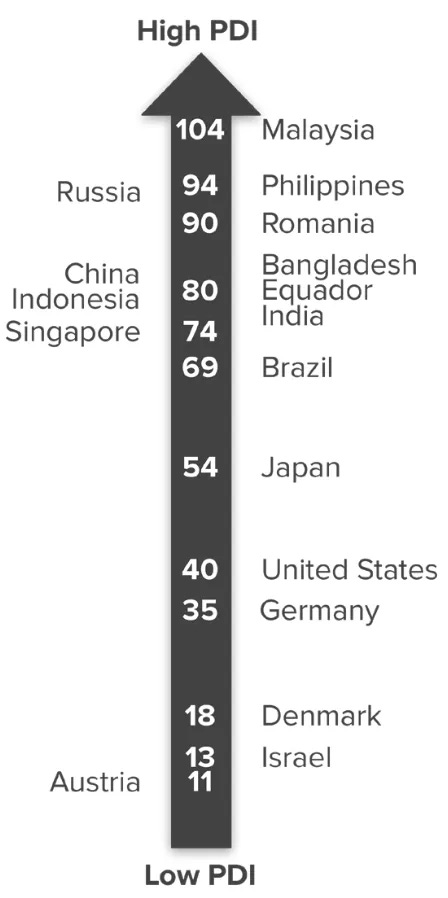

Geert Hofstede’s study of power distance in business culture helps to demonstrate the disparity in how we communicate. His work modeled the distance between different cultures, as shown by his Power Distance Index.1

The impact of this distance has been the subject of a study by the University of Waterloo. In the study, Chinese and Canadian participants were instructed to negotiate a business contract. The study found that misinterpretation in the meeting was common. For example, Canadian participants would conclude that the meeting went reasonably well when the Chinese participant had radiated open hostility. It was a misunderstanding of cultural cues: When the Chinese participant sat back and assumed a relaxed appearance, and made frequent eye contact, the Canadian saw acceptance — essentially, being at ease and open to negotiation. Those cues were misinterpreted. In Chinese culture, they signaled a lack of respect, disdain, and even open hostility. A respectful posture would be sitting erect, and not making excessive eye contact.

Cultural cues vary dramatically from one culture to another, and most people are predisposed to blithely ignore what isn’t immediately recognized. The Indian head waggle is a great example. Because it’s not a Western behavior, Westerners assume it means nothing. In fact, it can mean, in a uniquely unenthusiastic way, “Yes,” “Nice to meet you” and “I completely understand what you just said.” It can also mean “Maybe,” “Hell no,” and “You are the enemy of intelligence.” Interpreting it requires time, practice, and above all, a personal presence.

Communicating successfully

Every culture has its own unique characteristics. Beginning to build sensitivity toward different communication cues is pivotal for anyone working in a global context. Probably the most important single step is developing an awareness of our own culture. With this awareness comes a sensitivity to things that don’t fit. For example, simply being aware that you don’t know what an Indian head waggle means can prompt you to ask “what’s going on?”

We can also slow down communication when cultural boundaries are involved. Americans tend to fall back a their desire to “move things along,” and stick to a tight schedule — while Indians tend to speak very, very fast (often too fast to understand). Instead, if we don’t rush, if we slow down, the other party will have more opportunity to notice those cues that should signal there’s more going on.

As Jack learned the hard way, the feet are considered unclean as the lowest part of the body. In Asia, feet should not be used to touch things: Don’t closing a door or put them up on a desk. Just pointing your foot at someone is extremely distasteful. Having the sole of your foot facing anyone can be a rude insult or, at least, unforgivably obtuse. To be safe, make sure your feet are flat on the ground at all times.

The best thing to do is to get some exposure early. Develop some sensitivity to your own cultural cues, and try to explore your host’s cultural preferences. This could be a vacation, or a coaching session, or even a conversation with a friend from that culture. Above all, avoid jumping in blindly and thinking the business culture of another country is going to be just like home.

Impact on business

Culture and marketing is riddled with stories about how one particular foreign ad campaign or another was a spectacular failure. Gerber ran into a problem because, in some cultures at the time, women had low literacy rates (such as Africa and the Middle East). The women in these cultures generally used pictures to tell them what food they are buying. When the company’s products were introduced in these countries, sales were poor. It turned out that the traditional packaging, featuring a picture of a baby on the food jar, did not translate well to the local culture.

I’ve frequently heard from internationally-engaged teammates that their overseas partners don’t communicate clearly. They might tell me, “They never give us any feedback.” Perhaps they say, “We always come to the table ready, but our partner just keeps talking – they never want to start anything!”

Listening to them, it seems they understand that communication as the cause of misunderstandings, tension, and problems across their organization. What they’re missing is that communication is not just words for most cultures.

Sometimes I’ll hear about logistics issues of a distributed organization, or possibly social cultural issues (such as how to greet someone). Most of the time these are casually dismissed as being a minor stumbling block, and the topic comes back to how terrible their international partner is at direct communication.

High and low context

The United States is a decidedly “low context” country when it comes to communication. The term “low context” simply means that communication is direct, relying chiefly on words to deliver a message, not other contextual communication cues.

It turns out this is typical of countries with diverse cultures — that is, a people assembled from widely varying, disparate backgrounds. These “melting pots” tend to develop low context communication styles because of that extensive diversity. The diversity brings together communication styles and practices from a vast, widely differing array of cultures, each with its own specific ways of communicating. That great diversity of culture and communication styles makes it difficult to develop a common set of signals everyone can understand.

The United States is an excellent example of such a culture, having been born out of an amalgamation of cultures from across the world. The large number of rich cultural groups required a unique intensity of low context, direct, simplified communication. In fact, at least some of this simple directness is a residual effect from the early pioneer days of this young country: When immigrants speaking a variety of different languages where thrown together, often speaking a common but halting English, plainness and unsophisticated language won out. A simple, if well-used cliché became more understandable than an elegant argument or an original expression. The culture of the United States never recovered from those exigencies its early history. Even today, speech tends to be fast, but simple and clear. The “working man’s” speech is reminiscent of the “Old West.” This direct communication is highly effective in delivering its message. The popularity and heterogeneity of American television attests to it: Easy to understand speech is direct: Anyone with a basic understanding of English has a good shot at enjoying the show.

But there is a cost to this simplified form of communication. There is a feeling that “everything must be said,” because if it isn’t communicated in words, it won’t be communicated at all. The corollary is that everyone must be open to hearing the message, and so phrases like “don’t take this personally,” and “to be honest” are used to soften a direct message. There are few alternatives available to an English speaking Westerner — especially an American.

And that’s the root of the problem: In the global context, everyone is definitely not open to hearing the message in such a blunt, direct way. Just consider that the population of Western Europe and the United States represents only one tenth of the world population. It’s unlikely things will change soon — so we can reasonably expect Westerners to experience problems abroad.

How most of the world communicates

“High context communication” means that more than words are used to get an idea across. The high context communicator relies on a host of methods to express themselves. These include body language, eye contact, over- or under-confirmation, timing, silence, story telling, the location or venue of a conversation, tone of voice, choice of vocabulary, personal appearance, formality and respectfulness (or lack thereof ), and even smell. High context communication means rich, often subtle, and frequently complex communication.

Many languages support this rich communication style by introducing methods of speech that convey additional context. Latin languages add masculine and feminine noun forms, and almost all Asian languages have several layers of formality, ranging from the familiar to the respectful. In some instances, multiple layers of context are present, giving the speaker honorifics, formal address, and integrating power distance into the language itself.

This rich communication evolved from cultural roots that are thousands of years old. BRIC countries prefer this style of high context communication. They are formal communicators and prefer indirect communication over the simplified messages of the West. Americans miss important signals because they are only listening to the words, ignoring so many messages, and hence come across as “blunt, rude, and often inappropriate” in their dealings with other cultures.

Formality plays an important role. Using a proper form of address, much like a “Sir,” or “Professor,” and giving deference to the eldest of a group (or a superior) conveys respect. Lack of such honoraries conveys disrespect. Many high context cultures also tend to think of the group — the family, the team — before the individual. Singling out the individual then excludes the group. Some cultures think so strongly of the group that individual performance is never discussed in a public forum, and rarely discussed directly even in a private setting. It becomes the group’s responsibility to support the individual internally. Think of it this way: Singling out an individual with a reward is indirectly putting everyone else down.

Eastern Asian cultures are among the most developed when it comes to sending a message, often using words that seem to have little meaning in the message. Language is used as a means of communication, but it’s what is not said that carries the real meaning. The most important context, desires and feelings, are conveyed by the manner of the conversation. Smiles, pauses, stories, sighs, nods and eye contact convey everything, while the conversation turns to apparently innocuous pleasantries. To those able to pick up on these signals, communication is rich, varied, and powerful. But those that are blind to the signals feel left out of the loop, in the dark, and become confused by decisions that seem to happen without any open discussion.

But, just as Westerners have problems in these high context, predominantly Eastern cultures, the reverse is also true. The high context communicator can be just as lost when trying to use simple, low context tools. Many individuals coming from a high context culture struggle because English by itself can often seem bereft of a means to express ideas. For example, Japanese will likely feel uneasy addressing an elder superior without the language structure that conveys respect, age, wisdom, and seniority — and yet, those tools don’t exist in English. To make matters even more uncomfortable, the casual, direct nature of most Americans probably means they’ll ask to be addressed, simply, by their first name. “How,” they might ask, “can I possibly know everyone’s role and relationship in such a culture?”

I hope you found this first part of the post interesting — multicultural communication is a complex area. In the second half of the post, I’ll talk about how we can become more adept at communicating in a global workplace and hopefully offer a few tips that make working with an international team a little easier.

If you find Customer Obsessed Engineering and the Delivery Playbook valuable, please share it with your friends and coworkers.

Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. Revised and expanded 3rd Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill USA, 2010. ISBN 978-0-07-166418-9.