How to fix a $25 bug before it becomes a $37,500 problem

Stop debugging and start designing by "shifting left" with BDD. It's not about testing. It's about feedback loops and thinking clearly about intent before diving into implementation.

As I wrote Chapter 3.6 of the Delivery Playbook (and it started getting too big), I realized the outsize importance of Behavior Driven Development. It’s fundamental to the playbook. It protects product and customer value throughout the software lifecycle. So I decided to split this out as a companion article. I hope you find it as essential a practice as I do.

The incident

On June 4, 1996, the maiden flight of the European Space Agency's Ariane 5 rocket ended in catastrophic failure. About 40 seconds into its flight sequence, at an altitude of about 3,700 meters, the launcher veered off its flight path, broke up and exploded.1

The cost for this failure was estimated to be $370 million. The rocket was carrying four satellites intended to study the earth’s magnetosphere. Because of the payload’s destruction, building new satellites delayed scientific research into the magnetosphere for four more years.23

An elaborate and careful investigation into the cause of the failure was conducted.

While several factors led to a cascade of events, it came down to a data conversion error — an error that would have been caught in testing.

Unfortunately, the internal SRI software exception that caused the problem was never tested. Or, more specifically, it wasn’t tested in the Ariane 5 configuration. The failure resulted because Ariane 4-era software that used 16-bit signed integers had been plugged into a more modern system — a system that used 64-bit floating point data. The older Ariane 4 SRI software couldn’t cope with the new data format.

That’s the technical reason.

There’s a more important lesson here. The real reason for the failure was human error. Somewhere along the line, a decision was made: the decision that the Ariane 4 SRI module didn’t need to be retested in the new Ariane 5 configuration.

The investigatory board pointed to an underlying theme in Ariane 5 development as a root cause, that theme being, “that software should be considered correct until it is shown to be at fault.” The board took another view. Their belief was, “that software should be assumed to be faulty until applying the currently accepted best practice methods can demonstrate that it is correct.”

Systems must be tested to prove correct behavior. We cannot simply assume they are correct.

If you’re new, welcome to Customer Obsessed Engineering! Every week I publish a new article, direct to your mailbox if you’re a subscriber. As a free subscriber you can read about half of every article, plus all of my free articles.

Anytime you’d like to read more, you can upgrade to a paid subscription.

Preventable failure

The key takeaways from the Ariane 5 disaster are:

We cannot rely on software to be reliable unless currently accepted best practices demonstrate that it is correct.

Continuous integration and testing for correctness is necessary — even when correctness has previously been proven.

The Ariane 5 case is widely taught in software engineering courses as the canonical example of how a simple, preventable defect — discovered late in the lifecycle (during operation) — can have catastrophic and costly consequences.

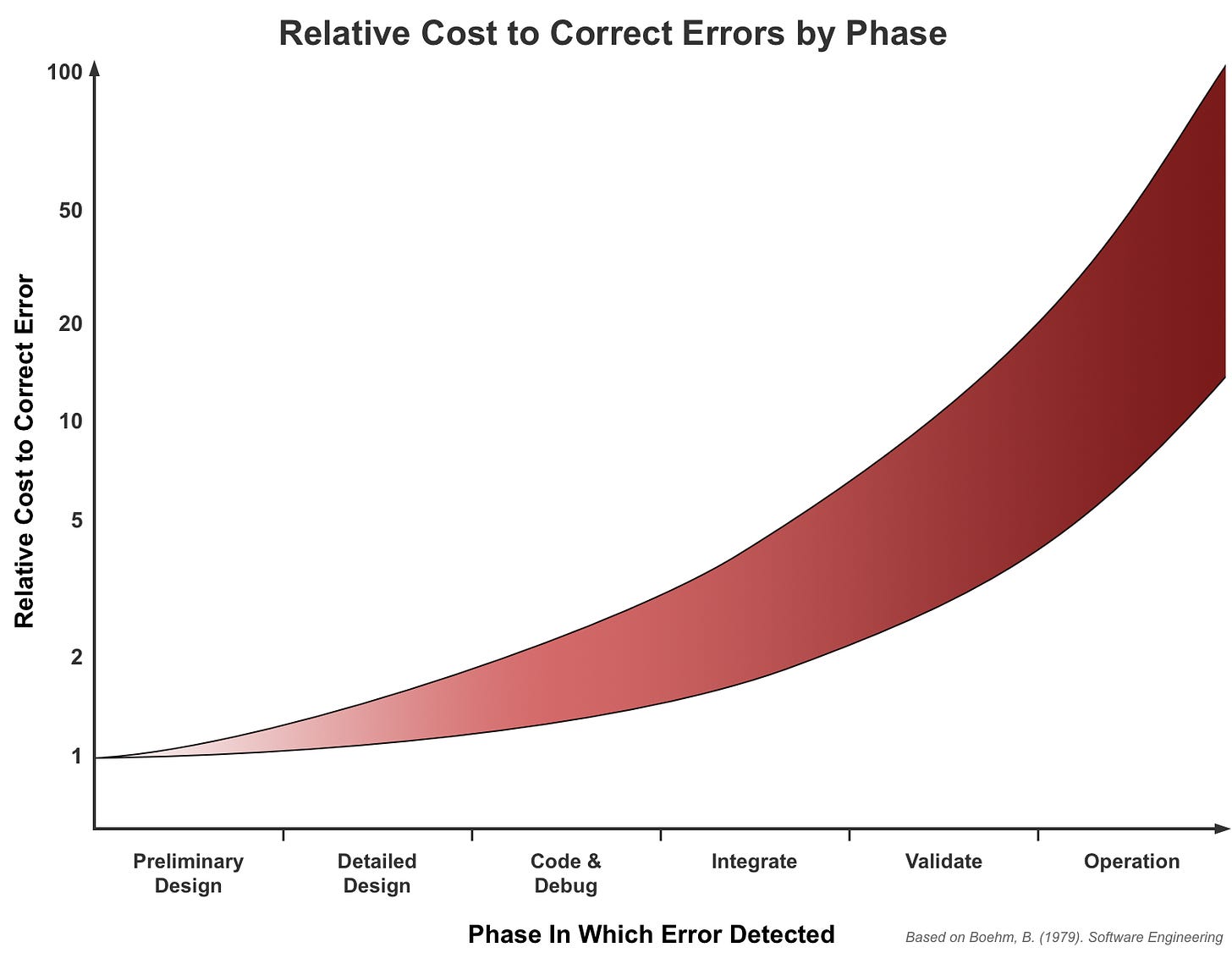

In fact, we know that the longer we wait to discover a defect, the more costly it is to fix. Research dating back to the 1970’s says we can fix a defect in design for nearly zero additional cost — or we can wait until production and spend north of 100 times the cost to fix it later (Boehm, 1979).

This exponential curve isn’t arbitrary. It reflects the reality that as software progresses through development stages, each defect becomes increasingly entangled with other code. Downstream systems begin to depend on it.

A requirements misunderstanding caught in design costs a conversation to fix. The same misunderstanding caught after integration means code rework, integration testing, release cycles, product updates and coordination across downstream dependencies. It can cascade into updating multiple products.

In concrete terms, that $25 defect can be fixed early, “for free,” or we can wait until later and spend $2,500 or more.

And there’s evidence that a 100X cost factor is by no means the upper limit. More recent research, in some cases, point to a factor of 1,500X cost to correct defects in operations. That $25 design defect just turned into a $37,500 cost to correct. There’s no upper limit — as the Ariane 5 team learned. (If you’re interested in reviewing more recent data there are references to NIST, NASA and Westland research in the footnotes).456

But there’s good news. We know how to prevent failures: By applying software quality assurance policies and practices — and pairing them with rigorous software testing.

Applying best practices

Test Driven Development (TDD) and Behavior Driven Development (BDD) are fundamental strategies to move defect detection left on the graph — ideally all the way to the design phase where cost is lowest.

Both practices create proofs that prevent defects. What’s more, they rely on executable specifications that prevent regression. Even after initial development, the test suite continues to catch defects early. A change that inadvertently breaks existing behavior is caught in seconds during the next test run — not discovered in production by users.

This ongoing protection is particularly valuable as systems age and original developers move on — the tests preserve institutional knowledge about intended behavior. Imagine how powerful it would have been if the Ariane 4 SRI module had included a continuously run regression test sequence.

The fundamental promise isn’t about testing — it’s about creating better designs. Both practices demand writing tests first. That forces thinking about how code will be used before thinking about how it will be built. This outside-in pressure tends to produce interfaces that are cleaner, more focused, and easier to consume, as well as code that is more reliable.

The deeper point

TDD and BDD aren’t really about testing at all. They’re about feedback loops and thinking clearly about intent before implementation. The tests are a byproduct — valuable, but secondary to the discipline of thoroughly articulating what you want before you build it.

Critics often attack the testing artifacts while missing this point entirely. It’s not always about going faster or whether every scenario needs to be test-driven. It’s whether your development process includes mechanisms that force clarity of thought and protect against regression. Both TDD and BDD are proven ways to achieve that.

I’d really, truly appreciate it if you could refer a friend. Writing takes a lot of time and effort. Your referrals make it worthwhile. And this button earns you free access!

TDD or BDD?

TDD catches implementation errors immediately. When you write a failing test before writing code, you discover mismatches between intent and implementation within minutes, not days or weeks.

The feedback loop is so tight that “debugging” often becomes unnecessary. When a test fails you know exactly what change caused it.

Compare this to traditional development where bugs lurk undetected until integration, verification or even user experience — by which point the original context has faded. Investigation becomes archaeological, time consuming and costly.

What TDD does well is clarify the boundaries of your system. Code that’s hard to test is often code with unclear responsibilities or excessive coupling. Even if you don’t achieve full coverage, attempting TDD reveals where your architecture needs attention.

But TDD has a limitation: it doesn’t “shift left” enough on our error discovery graph.

TDD is largely a technical exercise, focused on functional specification. As such it can get deep into the weeds of a feature — but may fail to rise to the level of product behavior. In other words, we might be applying our test-driven thinking to a conceptual design that is already defective.

That’s why I prefer BDD.

Behavior Driven Development

Behavior Driven Development is a collaborative approach that evolved from Test Driven Development. It bridges the gap between technical and business team members by expressing specifications as concrete examples, written in plain language everyone can understand (the “Given-When-Then” style, or Gherkin format).