Why you need a second brain

A second brain gives you superpowers, makes mental leaps that others can't fathom and finds information nobody else knows exists. Best of all, having one is effortless.

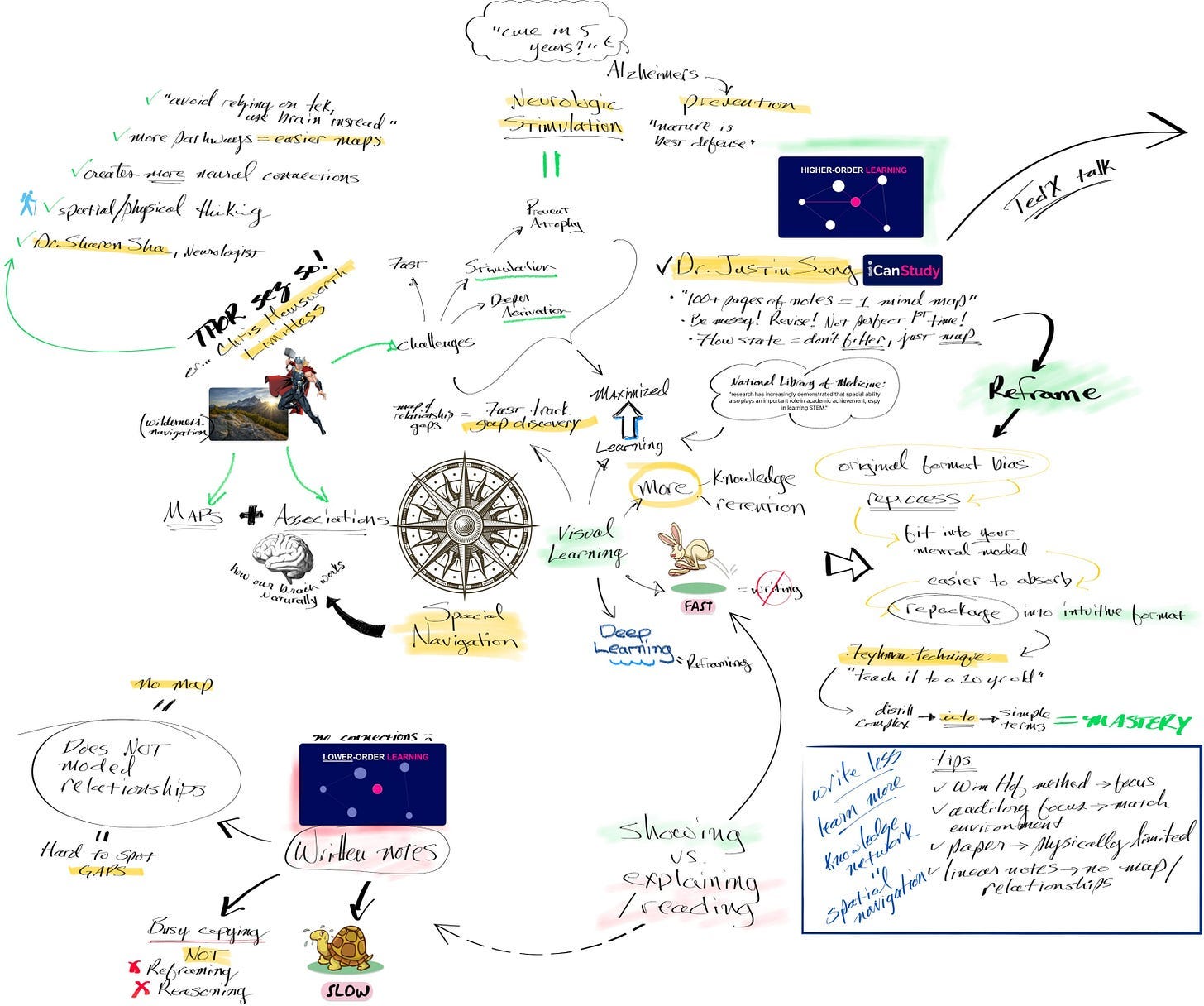

This article continues an earlier article, Transform the way you learn with spatial thinking & a second brain, which explores the benefits of spatial mapping to transform how we learn.

Turning facts into learning

In my previous article, I explored spatial mapping as a more advanced, more perfect way to understand new information. The human mind is a fanciful, imaginative, visionary thing, able to make leaps and connect ideas in unexpected ways. But it has limits, one of which is not being particularly good at cataloguing and uniting lengthy lists of facts. Unfortunately, that’s how most of us learned to capture information — pages and pages of notes, giving us little more than an undistinguished pile of facts to sort through.

Fortunately, there are better ways to manage knowledge — ways that work well with our brain. Our brains work best when conceptually connecting ideas, and they’re especially effective when we give them a visual, spatial map.

Shifting from a predominantly text-based method of learning to a visual technique lets our brain organize information more naturally. The part of our brain that connects things — visually, spatially — kicks into high gear. We start seeing associations more easily. The “visual map” helps us navigate our collected facts instinctively.

With a map, I can find information as easily as I find the kitchen and my espresso machine.

Taking it further, there’s an easy way to give yourself “knowledge management superpowers.”

Transformative thinking

Spatial mapping is a great way to capture knowledge. But what do we do with all of our spatial maps? It’s not enough by itself. Just a vast catalogue of mind maps would be impossible to manage. Each visual map contains a lot of information. We need a way to work with that information, not just look at it.

What we need is a “second brain” that digs through everything, turning it into knowledge we can use, quickly, effortlessly. A tool to actualize all that spatial information captured across multiple maps or other locations. A tool to discover the bridge between all those facts — paths to knowledge you would otherwise not tread.

I use my second brain every day to find obscure facts that I think I captured, but can’t quite remember. To see how ideas connect with others that I, personally, would never have connected. To turn a few passing thoughts into meaningful work. I use it all the time to pull up knowledge, giving me seemingly “instant” recall.

So, how do we create a second brain?

If you’re new, welcome to Customer Obsessed Engineering! Every week I publish a new article, direct to your mailbox if you’re a subscriber. As a free subscriber you can read about half of every article, plus all of my free articles.

Anytime you'd like to read more, you can upgrade to a paid subscription.

A digital brain

An effective second brain needs to extend your paper spatial maps into the digital realm, enhancing them with computer-driven analytics. That means being able to:

Easily mix images, sketches and text without limitation.

Map connections between things spatially.

Navigate through those connections quickly and easily.

Be unbounded and limitless when it comes to expanding our map of information.

Summarize, form connections, and collate for us “magically.” (Sort of like our subconscious does when we aren’t actively working on a problem).

Not that long ago, this would have been a near insurmountable list of requirements. Not so today. Today, there are plenty of apps that can get the job done — and more and more available every day.

To start, in this short video I showed how Apple’s Freeform app and an iPad provide superlative tool for capturing knowledge on-the-fly in a visual format.

But that’s only part of the solution. To effectively model our digital information map, we also need a way to electronically link facts together, navigate information, and work with that knowledge. Freeform is a great tool, but it doesn’t do everything we need.

What is a second brain?

We want an instrument that augments our natural abilities. Offload the things we find hard, so we can focus on the things we do well.

Compared to a digital system, our brains are not particularly good at remembering things, reminding us of what’s important when we need it, and finding specific details that we filed away ages ago. On the other hand, we are great at synthesizing ideas and creating!

Our brains want to connect things. The challenge is connecting to information that’s sitting inside our computer — in lots and lots of text files, snippets, bookmarks, pictures and links. How can we make sense of it all? How do we build our mental map so we can actualize all that potentially useful knowledge — information that’s effectively out of reach, because it’s buried in all those little files?

In 2022 Tiago Forte published Building a Second Brain. It’s heavily influenced by David Allen (of Getting Things Done fame). Forte applies the ideas of a second brain to GTD’s filing cabinets, and shows how it allowed him to overcome the limitations of his memory and mind. It’s a great foundation — and highlights the sheer effort that’s been invested in augmenting our natural capabilities.12

Tiago Forte introduces the idea of “PARA,” a way of organizing information. PARA stands for Projects, Areas, Resources and Archives, and as Tiago explains it’s an effective way to bucket everything, across your life.3

Building a second brain is highly personal. What works for some won’t work for others. For instance, I use Obsidian to manage information. As a programmer I tend to geek out on the technical aspects of what I can do with Obsidian — which, I think, is pretty awesome.

The trick is taking the core concept of a second brain, and building what works for you.

My Obsidian second brain

A second brain is a highly personal thing. It has to “click” with you or it won’t work, and PARA isn’t for me. I think it feels rigid, focused too strongly on categorizing things into their best place. It works well for some, but it’s not how I think. I don’t like bucketing information. For instance, I don’t file my emails into folders. I just archive everything and rely on really great search tools to find it later (Apple Mail has a powerful search language).

If you use the referral button below, you’ll earn free premium access to Customer Obsessed Engineering. Just three referrals will earn a free month!

Instead, I use a technique called “ACE,” for Atlas, Calendar and Efforts. For me, this is intuitive — it’s about where I conceptually expect to find all my stuff. I don’t really care whether it’s categorized in the right folder. In fact, I don’t like the idea of having to categorize things into folders, except at the most rudimentary level.

ACE categorizes information as knowledge-oriented, time-oriented, or effort-oriented.

For me, it clicks. My Atlas contains facts about — well, just about everything. If it’s information, it goes in the Atlas. Inside my Atlas I have a couple of very top-level categories: “Dots” are just random thoughts, “Maps” are my spatial and information maps, and there’s also “People” and “Notes,” the latter for anything that’s more elaborate and thought-out.

Then there’s my Calendar. This is my daily log, where I make notes about meetings, calls and activities throughout my day. It’s a simple format. If I need to record an activity, I put a daily note here, named with today’s date. One feature I love is calendar navigation: I can page forward and backward through my calendar, seeing the notes I’ve taken on any given day.

And then Efforts, which is where I put long-running projects that I need to organize. This is for client projects, my Customer Obsessed Engineering (COE) folder, really anything that falls into the category of a focused, specific, ongoing effort that deserves a home of its own.

I discovered ACE while trying to find the “right” way of organizing my thoughts. Nick Milo has a lot of interesting ideas, including this quick introduction to ACE. What I love about Nick’s method, Linking Your Thinking, is that it’s about building associations between information. That’s really comfortable for me — just like building a spatial map.45

How I use my second brain

Thinking about connections, relationships and maps is exactly what I do with my Obsidian second brain. It starts out very simple: